Danger abounds in the woods, and when you’re miles away from help, the risks are multiplied. In this article, Walter Arnold talks of some of the close calls and tough times that he and others faced over the years.

The Unexpected

First published in Fur-Fish-Game October 1944

Walter Arnold

Although one might roam the woods for a year without getting into any tight spots, he certainly cannot spend a lifetime there without finding himself in dangerous situations on more than one occasion. Things usually happen at the most unexpected times, and sometimes our danger is in forms undreamed of. Caution and good woods sense will keep a fellow out of a lot of trouble, but be as careful as he may, he will still get mixed up in scrapes, where if he had his choice in the matter, he would prefer to be most any other place – yes, even home under the bed. I think I felt that way one day when I was fourteen years old.

Log driving days

I was working on the drive, ‘sacking rear’, as they call it. (note: log drives were common on Maine rivers back in Arnold’s day. Large crews gathered logs harvested from the woods all winter long, and floated them downstream to the mills during high flows in the spring.) Several of us were picking off a center, while the rest of the crew were busily engaged along both banks behind us sending off the last logs. I made a spear at a log just as someone turned it and I missed. The peavey flew out of my hands and went to the bottom. I called out to the boss in the bateaux (boat), he took a look and said “There’s a bunch of logs just going past you, can’t you run ashore on them and get another peavey?” I took a look and figured I could. Drifting past were six or eight logs, three to five feet apart. I started running across them, but as I neared the last one I could see that it was much farther from shore than I had estimated. It was too late to stop, so I hit the last one and then jumped for all there was in me, hoping there might be shallow water near the shore. Nope, I simply went down and closed the door. Coming up, the current swept me into the alders and I pulled myself out. There were 35 or 40 men watching me, and they evidently liked my performance, for I got a great hand as I crawled out onto the bank. It was a long time before I heard the last of that ducking!

Bullets whizzing by

It was during a trapping season some 35 years ago that I was working up a small spring brook one morning. Danger was the last thing I would have thought of. Coming to a likely looking spot for a mink set, I bent over to start work when ‘Zip!’ over my head and ‘Slap!’ into a fir tree just behind me went a bullet. Had I been standing upright it would have taken me in the head or neck. I found out later a friend of mine, nearly a quarter of a mile away, had taken a shot at a fox running across the end of field near me. I probably had jumped the animal and came very close to jumping myself into serious trouble at the same time.

Down through the ice

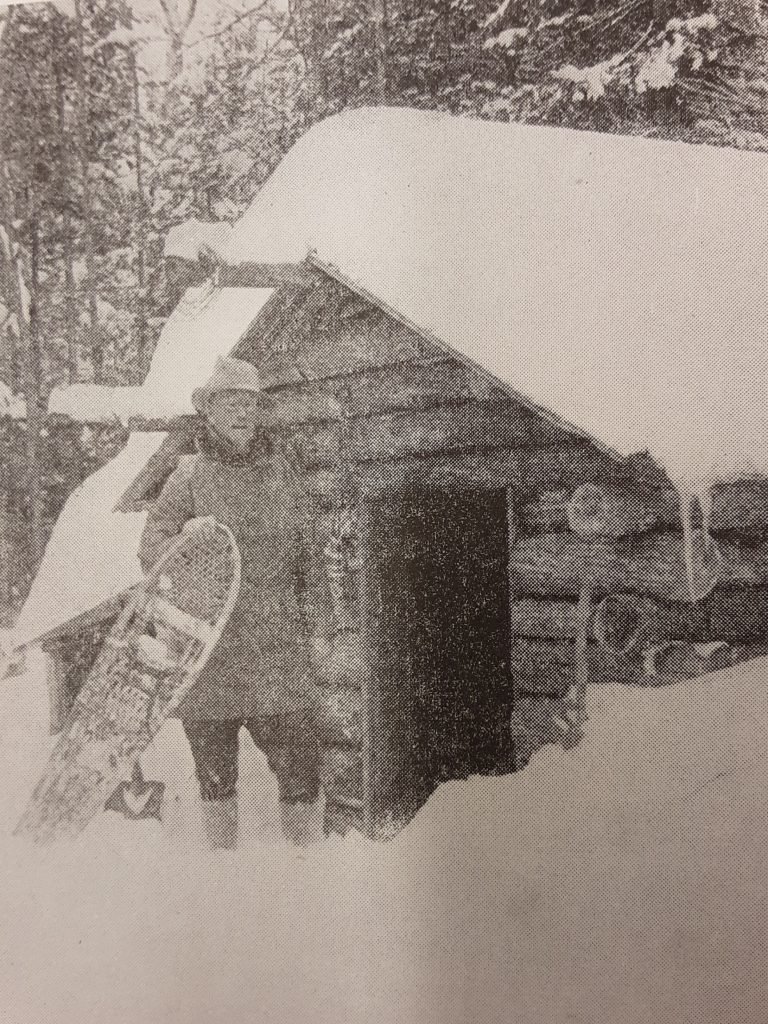

A friend of mine spends a great deal of time in the woods. He has had several close calls. Some years ago, Pete was trapping. One morning with the temperature around 20 below zero, he left his cabin, went down the hill, and started out across the bog. This is one of those bogs where a few bog spruce and juniper grow and most of the ground is floating with water holes here and there. Of course in winter, everything is supposed to be frozen solid. The winds had blown the snow off the main pond and piled it into drifts five to ten feet high on the bog. For some reason, he left the beaten snowshoe trail and started out across where he had not traveled before. Suddenly, without warning, everything gave way under him and he dropped through the drift into ice cold water. A water hole had thawed out under a big drift and the snow had melted away nearly to the top of the drift. More snow caved in on him and began getting wet, weighing down his snowshoes and hindering action. A look around showed him hopelessly trapped. He started clawing and flet something hard in the snow and soon found it was a small, half rotten spruce tree or pole. Putting as much pressure on this as he dared to, he finally worked out of water far enough to reach down through the snow and water and get his snowshoes off. Then carefully climbing up on the half rotten stick that meant life or death to him, he finally reached the top of the hard snow drift and climbed out. It was not over yet. Soaking wet and already numb with 20 below stinging cold, he had to make his way back to camp half a mile away. The clothes on his body were already frozen stiff when he reached it, and he found it almost impossible to get the door open with hands which had now lost their feeling, but he made it, and once inside the danger was over, as the fire was still burning in the old cook stove. A small, half rotten pole and a warm cabin saved him that day.

More gunfire

Some years later, Pete was out tending a trapline. Some careless hunter saw the bushes wiggling and let go two quick shots. The bullets hissed past old Pete’s ears. His temper was up in an instant, and he let out a yell and a curse. He heard the hunter take to his heels and run. This was too much for the old trapper. Cursing to the top of his voice, he took after the shooter. It turned out that the pursued was faster than the pursuer, which was probably a good thing for the former, as Pete can get quite mad, and is conserved to be a pretty fair shot at running game.

No, life for the trapper is not always smooth and rosy. If anyone had told me twenty years ago that I could go a whole week during the middle of the trapping season without taking a pelt I would have called him crazy, yet the time came, and I had out at least 200 good sets, when I ran into a slump, or shall we call it a crash? I never saw so many things happen before to keep game out of my traps. If a water set froze up, it was the one a fox came to and snatched the bait. If a rabbit or squirrel got into a trap, that was where the furbearer came. A bobcat came into an otter’s trail where I had a nice blind set with the pan of the trap at the side of the trail to take the otter’s foot, and the cat stepped onto the jaw of the trap. Another bobcat stepped into a #2 trap set for a fox, made three or four wild leaps, the drag caught fast and the big fellow pulled free and continued on his way. The state would have paid me a $20 bounty for that bobcat’s tail.

A squirrel shelling out a spruce cone attracted the attention of an unsuspecting fox about to step into a trail set. After an unsuccessful attempt to catch his dinner here the fox returned to the trail, but about 30 feet beyond the trap. That is the way things went. Although I had plenty of sets that were constantly in working order, they produced nothing. For thirteen days I did not take even as much as a twenty cent weasel pelt. I was taught then and there that we are sure of nothing in this world. Any idea I may have had about being a trapper was severely jolted around. Then, the fourteenth day the bad luck broke, and during the next week I took some of the best furs of the season, packing in some fancy mink, fox and bobcat.

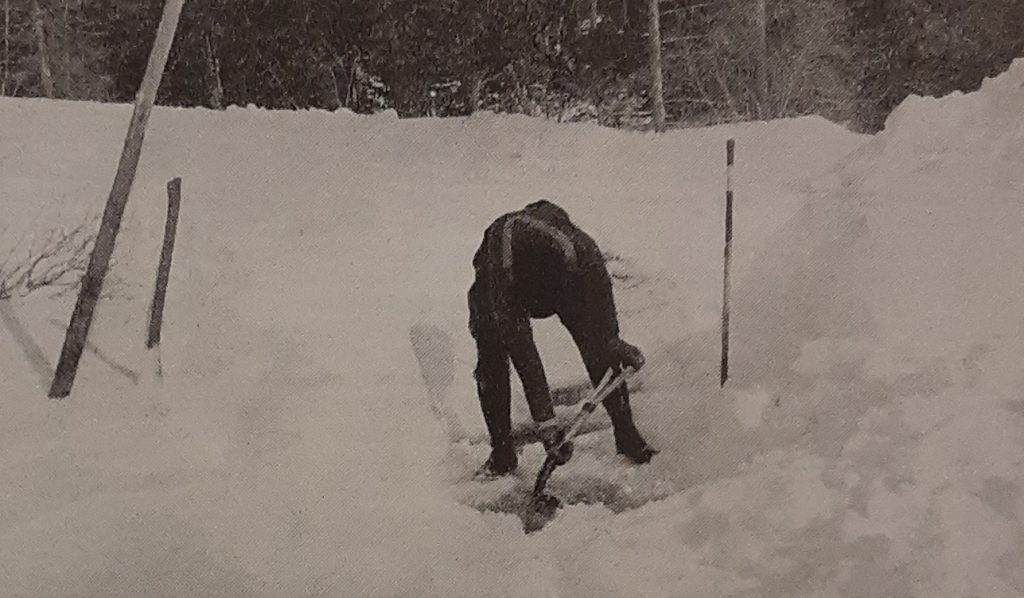

Trapped in the cold

Trapping in the raw and trapping on paper are two entirely different occupations. In the raw you never know what is going to happen, but on paper things can always be made to come out as one wishes. It was during our cold winter, I think it was ’35, that I encountered plenty of the raw. We worked day after day with the temperatures ranging from 10 to 50 below. Snows kept piling down, with some of the storms running to a 17 inch snowfall. We fought the cold and broke snowshoe trails until it seemed as though we could not go another step. We shoveled tons upon tons of snow, and the Lord only knows how many holes we chopped through three and four feet of ice in making beaver sets. If there is any romance or glamour in trapping, none was in evidence that winter. I certainly did not feel very romantic in one of the scrapes I got into.

Just before the final freeze up I had dug out a small opening in a beaver dam and put in a set using a #415 trap, which is made the same size and strength as the small bear trap #415-X. The 415 does not have any teeth, but the jaws come flush together. I fastened the trap chain to a sunken log back in the pond so any beaver that got in would soon drown. The beaver had been active around some under ice sets eight or ten rods up the pond, but none had touched this set. The temperature had been ranging from 10 to 50 below, so probably they were not fussy about trying to get their heads out into the biting cold. As I left camp one day to run this line, I glanced at the thermometer and the reading was 21 below. The temperature was accompanied by a savage northwest gale. I found as usual that the snow had drifted into a hard crust over the opening in the dam, and as I attempted to dig some of it away, the whole sheet collapsed into the water, springing the trap. when I got ready to reset it I found that by fastening the heavy chain so far out in the pond, I could not bring the trap up to the top of the dam where I would have a good foundation to work on it (it required both feet and plenty of strength to set this trap). In trying to reset it on the slanting edge of the dam, it slipped at just the wrong time, and I found myself caught by the thumb. I tried again to get it into a position so I could free myself, but it slipped again. Only my high rubbers saved my feet from becoming soaked.

There I was at the southern end of the pond with a 20 below zero gale pouring its wrath out on me. My mittens and pack were not within reach, and my hands were already becoming numb. There was no chance of getting the chain unfastened in a hurry, and I realized I did not have much time left. I decided to work on the trap as long as I dared to, and then if I was not out I would use my small, sharp axe, while I still had feelings enough in my hand, and with one swipe, clip my thumb off as close to the jaws of the trap as I could. I was out there alone and too many miles from any aid to take chances. I made another attempt and failed. Knowing the next would probably be the last try, I lay the trap in deeper water, nearly to my boot tops. I got my feet placed and put on the pressure, the trap wiggled around some but held, and in a moment my thumb was out. I soon had on mittens and made for the shelter of the nearby woods.

Swinging and pounding my hands until I had strength enough in them to light a match, I soon had a fire going. It was not long before I was back at the dam, and this time I saw to it that the trap was set right. I might add that the only thing I caught in that trap for the winter was my thumb! I did take the beaver in nearby under-ice sets.

Edge of the cliff

One day, an unexpected turn of events placed me in a position that had me worried for a few minutes. The time was mid-winter and I was working along the north side of a mountain gathering spruce gum. I came to a very large spruce, at least three foot at the butt. It grew right out of the very edge of a cliff, and leaned on a slant over the drop-off. There were some very nice looking patches of gum hanging from the underside of some of the first limbs, which were too far up to reach with a gum pole. The tree was much too large to shin, but after looking at the inviting slant I figured I could work up the top side to those branches. It was sort of a challenge. There was a thin covering of light snow on the tree trunk. Laying my pack, gum pole and other equipment to one side, I jumped up onto the tree and reaching around it as far as I could, started working up. I found there was a smooth coating of ice on the tree trunk under the snow, and then suddenly I slipped. The next instant, I found myself hanging down from the underside of the tree. Clinging for dear life, I slid back to the foot and now realized I was in trouble. Try as hard as I could, I found it impossible to to climb up on the top side of the trunk so I could get back on to the top of the cliff. Twenty-five feet below me was some snow, and lots of rocks and boulders, which were also probably covered with a thin coating of ice. It looked like an impossible task to reach the top of the cliff from my position, as the ledge was also slippery, but I went to work on it and put in one of the hardest fifteen minutes I ever went through. I do not know how I ever did it, but I finally succeeded in working up over the brink of the ledge to safety. I was young then and could stand a lot of hardship, but if that were to happen today I would never make it, and would have to drop and take my chances. Even landing on a patch of snow would not be safe, as it might be concealing a hole between boulders that would break legs. I was all of five miles from the nearest civilization. As far as I know, those tempting patches of gum are still clinging to that old spruce, and they can stay there!

Flood waters

Then there was the time, back in my early days of trapping, that I got mixed up with an October flood. Tucked away in the woods some six miles from home I had a very comfortable hunting and trapping cabin that was built to accommodate a party of six. I was camping alone and had just got the trapline into working order when my sister, who was a very good hunter, came in unexpectedly with one of her girl friends. They had been there about three days when my meager supply of food became somewhat depleted, and then it started raining. It rained all day and night and the next morning it was still coming down. Seeing as how we had to eat, I decided that I had to go out home and bring back a load of supplies. About halfway out, there was Shippond Stream, over which I had built a foot bridge. The water was rising fast and was getting close to the bottom of the bridge. I figured it would be taken out before the day was over, so hustled for home. I lost no time in loading my big waterproof pack and lit out on the return stretch. When I reached the bridge, the water was running against the last span, which was the lowest. I did not hesitate, but stepped on and started across, and when I reached the last spawn I stepped on the end and found it was afloat. I do not know just what had happened, but I think the horse had started to rise from the bottom with the legs still caught in the rocks. Anyhow, with my weight it settled, and the pressure of the water against it became greater and the next moment it had been swept off the horse. It started downstream in the fast swirling waters. This of course swept it off the horse next to the bank. Needless to say, the second I saw it going I started to run, and it started sinking with me. I got within six or eight feet of shore and then had to jump, which I did with all the power I had. I landed in a bunch of alder tops and got hold of them, dragging myself out onto the bank. I had held to my new Winchester rifle and still had the food. I would not say I was in any danger that day, as I was a very good swimmer, but had I missed those alders I surely would have had to shed the pack of food and probably discard my rifle before reaching shore.

The next morning the storm clouds had cleared away. I started out over my trapline, which took in several ponds. There was water everywhere. The ponds were overflowed, and at one of them the swamp land was flooded in places to a depth of three feet. I waded in water most of the day, and up to my waist at times. Some of my traps I could find, others I did not. There were a couple of fox traps with heavy wooden clogs, set in small brooks that I never did find, even to this day. It was after dark that night when I dragged my weary bones back into camp. My compensation for the day’s work? I had one grey back weasel which I later sold for the handsome sum of three cents. I was learning then that trapping was not all pleasure and profit.

Warden troubles

I might add here that it was some 25 or 30 years ago that two of our best Maine Game Wardens, who were supposed to know all about the dangerous setups nature can prepare and conceal back there in the big woods, set out together on a several days trip through some of the wildest part of the Maine wilderness, up near the Canadian border. It was winter, during a stormy period with very cold weather. They never showed up where they were expected, and soon most of the Warden force, along with guides and woodsmen, put in a long, midwinter search. Nothing was found, as snowstorms had covered all tracks. Nearly everyone believed there had been foul play, which created an international situation, as it was thought there had been Canadians crossing the line and poaching on Maine territory. As I remember it now, there was one suspect run in on some technicality just to hold him until the bodies were recovered.

Spring came at last. The violet rays from the sun drilled millions of fine holes through the ice, rotting it away while the warm air and spring rains whittled away the snow. Once the forest and lakes were freed from their winter bondage the hunt was on again in force, and soon the bodies were found in the outlet waters of a large bog. They showed no marks of violence. There is no doubt in the minds of most of us that the men dropped through a drift or went through thin ice into the water, and the subzero weather soon accomplished its work whether they were able to crawl out or not.

(Author’s Note: In November 1922, Maine Game Wardens Mertley E. Johnston and David F. Brown were investigating illegal beaver trapping on Loon Stream near Big Bog on the Canadian border. Their bodies were not recovered until the following spring. Official reports list their cause of death as gunfire. It is suspected that they were shot and their bodies were put under the ice by a Canadian trapper. As no other game wardens died in the line of duty during that era, this would have to be the same incident Arnold refers to in the above story.)

Pleasure comes with pain

Those who do not know what it is all about may think the reason a man is a trapper or woodsman is because his life is a continual round of pleasure. The reason most woodsmen and trappers are such is because they are men who can stand hardship, and after the hardship comes the pleasure. Mighty few know what it is to really enjoy a square meal until he has traveled or worked all day in the forest without food, and then in the evening reaches camp so hungry and weak he can scarcely stand, and then prepares a real meal after which he sticks his weary legs under the crude table and sits down to something he would not swap for all the riches in the world – he now knows the pleasure of eating good food. Then there is the pleasure of a cozy, warm cabin after one has been out all day in a freezing northwest gale, with temperature 30, 40 or 50 below zero, so cold that when he removes his boots a cup full of white frost as dry and fine as dry flour comes out of each boot, and he has been forced to stop several times during the day to break the ice from his eye lashes – the covering over the face throws the warm breath up and the moisture freezes to the lashes until sometimes you cannot see. It is then one will appreciate a warm camp. Warm, dry clothes? Well just try a day that starts out wet, by noon the weather has changed and everything is freezing and by dark it is 10 or 20 below and the clothes on your body are frozen. When you try to remove them at camp you find they have frozen to the hairs of your legs and you really have to tear the pants from your body – then you will know the pleasure of warm dry clothes.

Before a man really knows what it is to enjoy food, health, warm clothes, a good bed or a comfortable cabin he must first reach the trying depth of hunger, cold, sickness, sleepless nights and other hardships. No, trapping is not all a bed of roses, but just try to lead an old sourdough away from his profession.

Find this stuff interesting? I’m working on a book – a compilation of the works of Walter Arnold, the legendary trapper from the Maine woods. Stay tuned, and contact me at jrodwood@gmail.com to reserve a copy!

Leave a Reply