Boy, how things have changed when it comes to one of America’s most iconic furbearers, the beaver. Perhaps no other species has undergone such a dramatic shift in both economic value and abundance over the decades. Those up on their early American history know that the demand for beaver pelts was a major driver in the settling of the North American continent. The high value of beaver pelts and unregulated hunting and trapping led to a drastic decline, and near extirpation of the beaver in many areas by the early 1900’s and beyond. Beaver are a prolific furbearer, however, and restrictions on harvest for many years resulted in a huge comeback for the species. By the time Walter Arnold penned the article below, beavers had made an almost full recovery in many parts of Maine, and trapping seasons were opened up once again. Beavers were the most valuable furbearer trappers could pursue at the time, and most went to great lengths to trap them. Seasons were still quite restrictive, and trappers didn’t have a lot of the knowledge or equipment we use to harvest beavers more effectively today. Speaking of today, as I write this beavers are at perhaps the highest abundance they’ve been anytime in the past century, and unfortunately, their pelt prices are at an all time low. While they enhance habitat at moderate densities, overabundant beaver populations negatively affect habitat and cause flooding and property damage. In Arnold’s home state of Maine, we now have an almost six month season for beavers in much of the state and trapping regulations have been relaxed considerably to encourage the taking of more beavers. Still, they remain abundant. If only he could see it now!

In this article, Arnold discusses the state of beaver populations, the pros and cons (as he sees them) of having beavers around, and shares tips and techniques for trapping beavers.

The Beaver

First published in Fur-Fish-Game March 1948

Walter Arnold

Beaver Recovery and Conservation

Fifty years ago, there were but few of these valuable furbearers left in this country. Unrestricted trapping came very close to exterminating them all. Protective laws were enacted and in most cases, efforts were made to see that they were enforced. And today, we have hundreds of thousands of beaver scattered all over the United States. I would not care to go on record as saying there was a single state in which there was not even one wild beaver. They are found in such states as New Mexico, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Maryland, etc.

The 1945-46 catch in a few of the states reads as follows: Nebraska 9,180, Michigan 9,859, Texas 137, North Dakota 2,028, Maine 2,200, Iowa 623, Colorado 8,640, California 462, Montana 13,214, Missouri 25, Minnesota 9,477, New York 4,075, Nevada 884, Idaho 12,880, Arizona 368, New Hampshire 529, Pennsylvania 2,011, West Virginia 60, Wisconsin 15,250, and other states which had more or less open territory for beaver trapping. I believe that in most cases a whole state is not opened up, only sections of it. If the whole state is opened up, the number of beaver a trapper can take is usually limited to ten or less. There are many states having beaver in large numbers that will open up to trapping for a year or so and then close up again for one, two or three years. The fish and game departments of all states are watching their beaver very closely.

Pros and Cons of Having Beavers Around

Although they are very destructive with their cutting and flooding of timberland, I believe beavers are well worth the cost, as they net millions of dollars a year to trappers and the fur trade. I realize, however, that there are those who do not agree with me as the destruction is really far reaching.

For several winters, I had trapping exhibits at the Boston and New York sportsmen shows, and talked with thousands of people. Usually the subject was relative to trapping, and it was there that I came to realize how many there are who believe they know a lot about beaver, yet their ideas in general are the reverse from the real facts. For instance, there are many who still believe that beaver never lodge trees, that the trees always fall right where they want them to. They believe that when they build a dam it remains there as long as they need it. There are even a few who will attempt to convince you that these animals will select the type of trees that are of little or no value to the lumberman. Now we who have spent years among these animals know that these are not the true facts. Within a three mile radius of my home I can show anyone the remains of hundreds of timber sized poplar, yellow birch, maple and brown ash trees, some of which are fifteen or more inches on the stump – trees too large for the beaver to handle, the branches and tops being taken and the trunks left in the woods.

There is also the general conception that dams help to hold back some of the waters during floods. The truth is that as long as these dams are being used, they are kept in repair and are always full. When floods come there is little or no room for more water. Now and then the high waters rip out a dam, taking with it the water held back before flood time, and this can result in a lot of extra water added to the flood. Then again, it is usually during flood times that the abandoned dams give way, so instead of holding back flood waters they add to them. This addition, as a rule, is negligible, but certainly can not be called an aid in holding back flood waters. I knew of one flowage that ran back through three ponds for a distance of four miles or more.

There are those who maintain that beaver dams improve the trout fishing. It is true that the first year or so there may be excellent fishing, and under the right conditions it may continue that way. But as a rule, go back in three or four years, and chances are that every bush and tree has been killed by flowage and is rotting away in and out of the water, with the whole flowage becoming a foul, stinking filthy hole. That is what many of the smaller beaver ponds turn into. I have seen too many of my favorite trout fishing holes completely ruined to say that beaver dams, in the end, improved my trout fishing.

Now on the credit side for Mr. Beaver, we know there have been many instances where forest fire fighters have used the held back waters of these dams to great advantage, and this is especially true since the light weight portable pumping outfits have come into use. When conditions are favorable, water is forced a long distance to the scene of the fire. Forest fires occur when most of the brooks are nearly dried up and a beaver dam full of water is a valuable asset. I believe that thousands of acres of valuable timberland have been saved because these reservoirs of water were available.

Back thirty years ago we had a great many deer back here in the real wilderness sections of the state. The kill in many of these places was light as there was too much hard work involved in packing them out. My trapping grounds are back behind mountains and it is more than a deer is worth to drag one out from there. Deer were plentiful there both summer and winter, and then there became a gradual change. We would see quite a few during the summer months, but in the fall after the heavy frosts their numbers would diminish. It finally came to a point where there would be only a few that remained in there during the winter. We were at a loss to understand what it was all about, but finally figured it out. Thirty years ago there were hundreds of acres of low ground around all the bogs, deadwaters and small ponds where was found an abundance of small cedars, the natural winter food of deer in this section. It was in these places the deer would yard during the winter months. Beaver started working into that country building dams and flooding the lowlands until today those places are just acres of desolation – nothing left but the skeletons of once green trees.

Now deer can eat fir, hemlock and other browse, but it would be like putting a healthy man into a cell and giving him plenty of drinking water and all the apples he could eat all winter. He might pull through if healthy to start with, but certainly would not spend a winter under such conditions unless forced to do so. That is the same with deer. This other browse does not provide the proper nourishment, so they move out as soon as the nice summer food is gone. Although deer hunting is not now nearly as good as of old in the real wilderness of northern Maine, it has improved in an around the farming localities where there is winter food more to the liking of these animals. We still have just as many deer in the state, but the kill has been shifting from the wilderness to the more thickly inhabited localities, at least the records show that.

There will be found places here and there in the big woods where deer are found in large numbers throughout the winter, but these are usually places where lumbering operations are being carried on and the woodsmen are cutting down plenty of all cedar and hardwood trees with large tops, which after brought down are within reach of the deer to feed upon.

There are those who claim that bear are driving the deer out, but to me this is not the answer, as I can remember back to the days when there were five times the deer in the big woods where I operate, and just as many or more bear than there are today. Furthermore the deer still go back there in large numbers during the summer – that is when the bear are also active, yet in winter afterafter bear are denned up and cannot bother, most of the deer have worked out into civilization. I do not think that bear have anything to do with this situation whatsoever. I do believe, however, that the beaver has brought about the change or has contributed quite a bit toward it. He should not be condemned for this as the records show that the deer kill is holding up very well in the state and that there are many localities with excellent deer hunting today where ten or fifteen ears ago there was very little. Maybe I am wrong about this deer business, anyhow those are my conclusions and I am going to stick to them until I hear something more logical.

Traps for Beaver

The sets employed in taking beaver are many and varied, but there are three or four which take most of these animals. But first a word about traps. To hold sixty or seventy by the hind foot, one should use very strong traps with teeth, such as the #14 Oneida Jump. The hind foot of a beaver is smooth and flat, and as tough and slippery as any leather. When a big beaver is obtained, select the strongest smooth-jawed trap in the outfit and snap it onto the hind foot and see how much strain it requires to pull it off. You will have your proof there. A good #2 Victor coil spring will hold the largest beaver by the front foot, but like the muskrat it may soon wring off.

Although the average beaver may pay little attention to a new trap as it shows up through the water, it is advisable to color all traps, as a few of the big sly fellows, the ones we like to catch, know what a trap is when they see one. Traps may be colored by boiling in a strong solution of alder and maple bark for an hour and then left in the solution for a couple days.

Scouting

If winter trapping is to be done it will pay to look over all beaver territory you plan to trap some weeks before the freeze-up. At each colony, hunt out all the most used drag-in trails where they are bringing wood into the water. Locate the best places to make under ice sets at the mouth of each trail and remember exactly where all these places are. Beaver will come up and visit these places for sometime after everything is frozen over solid. Do not let distance stop you, even though a trail may be fifty rods from the lodge and feed pile. Usually the largest beaver in the colony can be taken at these sets. However, do not let anyone kid you into believing that only small beaver are taken twenty-five or thirty feet from the house, large ones are taken there too. I never did have much success with sets made right in the brush of their own feed piles. Search carefully and see if you can locate any holes they have dug into the bank, under water. Sometimes such holes will be found many rods away from the house. Later in the season when a small army of trappers hit the place, chopping ice and making a lot of disturbance, and taking now and then a beaver, the last one or two may get scared out and take up quarters in this specially prepared place of retreat. Oftentimes the trapper who knows where such places are will take a couple nice pelts after the other trappers have given up.

Competition

When trapping where there is keen competition, keep a careful watch of all traps which are set on poles where one end of the pole is above the ice. Quite often one of those ‘scum of the earth’ trappers will make a business of going around when you are not there and hitting the side of the pole a stiff blow with a heavy axe, which will often spring the trap on the pole under the ice. A dirty trick, practiced by a dirty trapper. This same two-faced piece of humanity will also slip a piece of wood under the pan of a trap so it cannot be tripped by an animal. If you think someone is cutting open a hole when you are not there, place a tiny stick where it will freeze in across the hole. Look for it when you come again.

Scent and Trap Placement

Open water trapping for beaver is quite simple, but that does not mean that one should leave everything about the set smeared with human scent. Traps may be carefully concealed in small brooklets leading into the main body of water, or under water where their drag-in trails enter the water. Traps should be at least one inch under water (four is better), while seven is more likely to take a hind foot. The pans should be an inch and a half, or more, off the center of the trail, as beaver (like otter) travel wide with their legs apart. Sets at dams, where legal, are very effective. A careful inspection should reveal one or more well worn places where these animals climb up over the dam when going downstream or coming back. Place the trap between one and eight inches under water, either above or below the dam where these crossing places go over. It is not necessary to disturb the dam. No bait or scent should be used at any of the above mentioned sets. Camouflage the trap a bit with a few water-soaked leaves, grass, ferns, mud, etc., that are right there at the time. Do not overdo this, as it is all right if parts of the trap are visible.

A good scent is used with excellent results at sets made where beaver are not already working, such as the side of a rock, hassock, stump or log. One or more traps are placed at the side of the object and a few drops of scent placed on the object close to the trap. Such sets can usually be made so that other trappers are not near as likely to see them, and if made where beaver will pass close by, are just as effective as any other type of set.

Holding Trapped Beaver

Remember, if caught by the front foot, beaver can wring off as quickly as a muskrat. In shallow water sets it is a good idea to really try for a front foot catch and use a light trap like the #2 Victor coil spring, as they cannot get the purchase on this that they can on a large, heavy trap. Check your traps early in the morning. It is also well to use six or eight feet of telephone wire for extra extension chain as this will allow them to move around more, until hung up, and prevent many wring-offs. Heavy weights are often fastened to traps so as to pull the catch down into deep water where it will drown. That works all right if the animal goes directly to deep water and is pulled down, but if it does not, the heavy weight only aids him in getting better purchase so he can twist off more quickly.

Open Water Beaver Set

A nice open water set is to find a large tree or log that lays with the butt on land and the top out into and under water. Fasten chain to a tree. Cut a slanting, downward gash into the branch so a small piece of birch bark or other noticeable item can be stuck in just above the water. Place scent on this object. In case the upper side of the log or tree is not sunken it is often easy to fasten two short, strong sticks to the underside of the log so they run out eight or ten inches and about five inches apart. The trap is fastened, very lightly, with a fine wire or string and is usually between two and six inches under water. Now with the axe, hew off a chip from the side of the log over the trap, making a bright spot on which some scent is smeared.

If the log is limbless or dangerous to get out on, find a long pole five or six inches in diameter. Place one end on the shore eight or ten feet away from the log and run the other end out across the log where the log submerges under water. Now fasten the pole so it will not roll. Go out now and cut a notch in the big log just beyond the pole that lays across. The whole procedure should be executed so that when the trap is placed it will be at least one inch under water (four inches is better) and about six inches or more beyond the pole. Now cut a tempting, small food tree about one and a half inches at the butt and fasten it to the side of the log so that it runs out over the cross pole with the lower branches of the food tree out at the cross pole and the brushy top well beyond the trap. Get another food tree the same size and run out on the other side of the log and the trap. The lower part of the brushy tops should be in the water. Get a small evergreen bough that will fit snugly within the jaws of the traps and fasten to the pan of the trap. Mr. Beaver comes up and snips off some of the top branches, then about the second night, decides to cut one of the trees off at the cross pole.

Shallow Water Set

One of the best shallow water sets is to fell a bushy topped food tree into the shallow water, or go back into the woods and cut a large moosewood, or small birch or other food tree and drag it down and place with the top in the shallow water. Fasten the trunk of the tree securely. Place three or more large traps, such as the #14 Oneida Jump, within a radius of five or six feet, under water in the brush, so when a beaver gets into one he will soon get into more before footing himself.

Under Ice Beaver Trapping

Winter trapping under two or more feet of ice is a task which taxes one’s patience and skill. Needed is a good chisel and axe. A skimmer to remove cracked ice from the water and sometimes a shovel will come in handy. To those who have never attempted to chop through three feet of ice covered with several inches of slush, with an axe, I will say they have missed an instructive bit of experience. Under ice sets may be anywhere from twenty-five to several hundred feet from the den or house. Traps may be placed several feet under water, but it is far more desirable to have them eighteen to thirty-six inches under the ice. Success in under ice trapping depends much upon being able to select places where the sets are placed where the beaver are most likely to be swimming. Beaver are not always easy to take under the ice because they have a very comfortable house to live in and loads of good food packed away at their very door. It is often not until this wood becomes sour and slimy that the real shy ones will take chances.

A trap-shy beaver is sometimes outwitted by dropping four or five evergreen boughs, a foot or more in length, down onto the bottom under the set, then find a soft, fine, well filled bough about six inches long and as wide as the trap and fasten same to the pan.

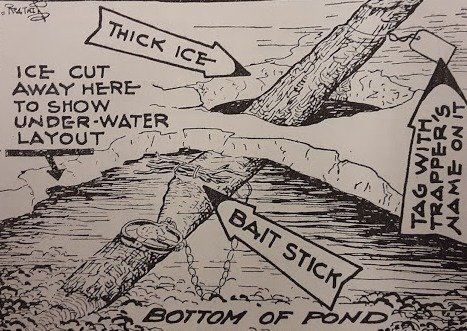

There are many different under ice sets, but I am going to explain only two here, which will usually clean up the beaver in a colony. In fact, the slanting pole or log set is the only one used by many experienced trappers. There are variations to this set, but the following is the general procedure.

Cut a log six or eight inches in diameter – wood that beaver will not eat, such as fir, spruce, cedar, etc., or any dead dry wood. Length will depend upon the depth of water. Sharpen the butt and then push down through a hole in the ice (which is about one and a half feet wide and two and a half feet long) and into the bottom of the pond. It should be at a sharp slant, as indicated in the illustration. After it is found how far it can be shoved into the bottom and the depth is estimated, pull it out. Cut a deep notch into the log, one upon which the trap can be placed, and at a slant so when the pole is set into position the trap will set about level. The upper scarf of the notch should be long, so it will not interfere with the closing of the jaws of the trap. Now, above the trap, nail or wire on a tempting piece of food wood, or bind on a bunch of tender green branch tips such as moosewood, brown ash, maple, poplar, wild apple tree or other favorite food. The bunch should be trimmed so it will not be much over a foot long.

When competition is keen and you want to keep something extra, make up two large bunches of limbs and twigs. Then, instead of putting on the single bunch crosswise, put these two on with the butts crossing each other up at the top of the scarf and adjusted so that a good large bunch of tempting food runs down past each side of the trap. Do not trim these bunches. Sometimes it may be necessary to hew the top of the log flat above the scarf so the bundles will fit on better. Oftentimes I have found it more convenient to have the loose brush handy and, using just two or three branches at a time, bind them on with stove pipe wire. Two or three on one side and then on the other until a good lot is on for bait. The more brush on there the better it will look to Mr. Beaver. When the bait is on crosswise it should be six or seven inches above the trap. When the pole or log is set back into position the bait on it should be ten or more inches below the bottom of the ice, but not so far down that it cannot be seen when you wish to inspect your trap on return trips.

A couple shingle nails driven into the scarf in the right place will hold the trap in place, but never fasten a trap so a beaver will not quickly pull it free, as he is very apt to foot himself before he drowns if the trap is held solid. The trap may also be held on by using a very fine wire, or even twine string to bind it on. Sometimes the pole is not large enough to make a large scarf in and the proper trap place may be made by nailing on a small piece of wood, at the lower lip of the scarf.

When tending under ice sets, the beginner will soon find that when he first lays down to look into the holes he will not be able to see anything. It sometimes requires several minutes to get the eyes focused to the different light. Using your hat for a shade will often aid in clearing up your vision. A strong flashlight that will focus into a narrow beam will also help a lot. The trap ring may be fastened securely to the back of the log. As this set usually takes the beaver by a front foot, the most popular trap is probably the #2 Victor coil spring.

When there is not over a foot of water under the ice, one of the best sets is made by cutting a hole a foot or more square through the ice. A poplar, moosewood, brown ash or other food stick from three to five inches in diameter is driven down into the mud. If not driven down securely a beaver will cut it off just below the ice and go with it, but if secure he must drop to the bottom where the traps are in order to cut it off there too. One or more traps are placed around it with the pans seven or eight inches from the pole. Usually it is advisable to drive down a couple small dry poles back of the food pole so as to keep the beaver on one side, then the trap chains may be worked around back of the dry poles and the telephone ire run up to the top of the ice and fastened to a log or what-have-you. This will prevent the animal from hitting the wire and displacing the trap before getting into one. With the chisel, try to work some mud or leaves over the traps. A real tempting bait at this set is to bind a big bunch of fresh sprouts or limbs to the pole and push this down so that the broken ends of the bunch are in the mud, the tender ends sticking up toward the ice. When in this position, a beaver cannot cut them off without dropping down to the bottom where the traps are.

In some states the law prohibits the setting of traps at beaver dams, even when beaver trapping is allowed. I believe that the main reason why such a law becomes necessary is because so many trappers do not realize the ill effects of cutting or tearing out great holes in a dam, draining out all of the water in the pond. In such cases, after winter has really set in, it is seldom that anyone takes many beaver. Contrary to the belief of many, beaver are not likely to come down and repair large breaks in the dam after everything is frozen up solid. Furthermore my experience has been that if a house is 150 feet or more from the dam they are not likely to come to the dam for any reason during winter where there are a couple feet of ice and the temperature is hanging around zero and lower.

When winter sets are to be made at the dam, find the main spillway. It may be necessary to cut away a little of the ice so the trap can be placed three or four inches under water on the upper side of the dam. The trap should also be placed so that the pan is an inch and a half off center, or where they will come up so as to engage the front foot and not the body. Don’t dig out any trench, but if there is loose brush or sticks in the spillway which ice will collect to, remove them. To prevent wring-offs, cut a small hole through the ice back in the pond about four feet from the trap and drive a solid stake (that beaver will not eat) down through and into the bottom of the pond. Put an extension wire onto the trap chain so the trap will reach back a couple of feet beyond the stake when a beaver starts out with it. He will soon wind around the stake, which will hold him there until expired.

Scent and Castors

Always use a good scent at sets where you wish to call a beaver into a trap where they have not been working. Do not use scents at sets where they are coming every night, as in such cases it is something new and may put them on their guard.

Always save the castors from the beaver you trap. These are found just under the meat, one each side of the vent. The beginner can easily locate them by feeling around the vent of the skinned out carcass. They feel hard, like chunks of wood. Cut around these and pull them out, vent and all, then proceed to skin the meat and fat from them. On each castor will be found an oil sac. Carefully remove this from the castor without cutting into it. With a little practice, one will soon learn to clean up a pair of castors so that they are still attached together. Oil sacs are also cleaned and usually left together. Hang castors and oil sacs up in a shed or other airy place where they will dry. It requires nearly a year to thoroughly dry out a large pair of castors, but the outsides will dry off sufficient in a week or so to stand shipping. The oil from the sacs may be drained out into a clean bottle or jar. The castor is one of the best scent making ingredients, and there is always a ready market for it. The oil from the sacs has some value as a lure and is also a good base to hold the odor of other ingredients.

Hope you enjoyed this article. It’s part of a book I’m working on, covering the works of legendary trapper and writer Walter Arnold. Contact me at jrodwood@gmail.com to reserve a copy, and I’ll let you know when it comes out!

Leave a Reply