The way trappers think about scent has changed drastically in modern times. In Walter Arnold’s day, scent control was gaining popularity as a necessity for successful trappers. This mentality continued on through the fur boom of the 1970’s and ‘80’s, when every trapper and their mother wrote a fox trapping book, and scent control was continually stressed. From head to toe, all clothing worn had to be cleaned and scent free, and could not be used outside the trapline, lest it pick up foreign odor. Traps had to be properly boiled to remove scent, and all equipment treated similarly. The trapper knelt on a cloth pad to keep from spreading scent on the ground, and a minimum amount of time was spent at the set to prevent leaving scent.

Today, trappers are still somewhat divided on the importance of scent control, but far more trappers place minimal emphasis on its importance. In fact, there are many successful modern trappers who set traps right out of the box, bare handed, with leather boots kneeling in the dirt. And they catch lots of critters, including foxes and coyotes. What’s up with that? Was scent control never as important as we once thought, or has something changed since the early days of trapping?

A few possible explanations for the declining importance of scent control come to mind. It’s clear that during the most of the era when the old trapping methods were taught, there were far more trappers out on the land, and many more furbearers experienced being pursued by trappers and hunters. They associated human scent with danger above all else, and the smart ones (most of the dumb ones were culled from the population) learned to avoid humans, and passed that knowledge on to their offspring. Smarter critters meant that scent control was more important.

Nowadays, there are far fewer trappers around, furbearer populations are very high, and human population densities are higher. So, furbearers are used to seeing humans, but don’t associate them with danger quite so much. There’s no need to be smart, so both the dumb and smart survive, and overall the species (made up of more, dumber animals) is easier to catch, negating the importance of scent control. It’s just a theory, but it could explain a lot about modern day trapping.

Now back to the days when scent control was considered key. In this article, Arnold brought up an often overlooked, but potentially problematic form of human scent at a trap set: the breath.

Watch That Breath

First published in Fur-Fish-Game October 1933

Walter Arnold

Extreme caution is not always necessary on the part of the trapper to make it possible to outwit the general run of furbearers. Animals such as raccoon, skunk, wildcat, weasel, mink, bear, fisher, etc. can be taken with regularity even though some human scent is left around the sets. I will admit, however, that there are some trap shy animals of the above mentioned species that can only be classed with the fox or wolf, and then again there is an occasional fox or wolf that appears to be a plain darn fool, and walks into sets that no trapper would expect it to.

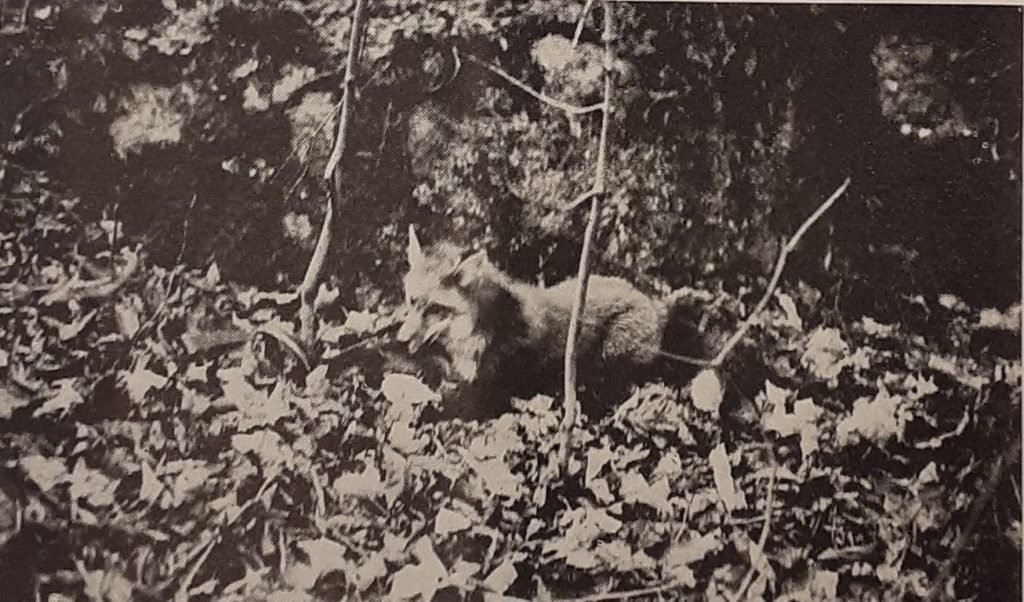

For instance, this past season I caught a full grown, healthy red fox that walked boldly into a big bough cubby house, after part of a rabbit I had hung up in there, and placed both front feet into a 31-X coil spring trap I had concealed there for wildcat. Such a case is really an exception, yet there are trappers (of course they may not realize it themselves, but nevertheless it is true) who try to make a living trapping by catching the exceptions. Sooner or later they must wake up to the fact that somewhere there is something radically wrong with their methods.

To really become successful in trapping fox, wolf, or other trap shy animals, the trapper must be capable of making sets without leaving evidence of disturbance around the sets, and leave them free from human or other suspicion-arousing odors.

To really become successful in trapping fox, wolf, or other trap shy animals, the trapper must be capable of making sets without leaving evidence of disturbance around the sets, and leave them free from human or other suspicion-arousing odors.

Volumes have been written warning the trapper of the danger of spreading human scent around sets through such carriers as the hands and feet, implements such as axes, trowels, hoes, traps clogs (drags), wires, etc., and from bits of cloth, tobacco, and other small particles that may fall from the clothes or pockets. In fact, every possibility has been covered and re-covered innumerable times, excepting the most important carrier of all. In my mind there’s no doubt the human breath is a carrier of as much, if not more, odor than either the hands or feet.

I can well remember the incident which was my first cause for this belief. On a lake near my home there is an island with an area of possibly an acre. One day, as I was passing by on the ice, I noticed that foxes were doing a considerable amount of traveling on the lake. On the back side of the island, close to shore, there was a trail where foxes had passed several times. There were several inches of snow on the ice and the tracks showed up plainly. The next day I returned and had with me in a new clean paper bag a clean trap free from any human or suspicious scent. I approached the island from the opposite side from which I wished to make the set. Part way across the island and from the top of a rock, I located a likely looking spot for the set. I then made my way carefully out to the shoreline. Along the shore there was a fringe of what I call pucker brush bushes about a foot and a half high.

With the trap placer (which was also free from scent) I reached over the bushes and made a very good blind a set in the trail, using no bait or scent. My tracks could not be seen from the fox trail in which I had set the trap, and I was sure that there was no scent about the set to arouse the suspicion of any fox.

To improve matters, there came that date a flurry of snow probably not more than ¼ inch, but sufficient to cover any slight disturbance I might have left. Possibly you can imagine my amazement the next morning when I arrived at the set and saw where a fox had come trotting down the lake and into the trail, and as he was about to step where the trap was, had turned and leaped away from the shore and ran for dear life out across the lake as though the devil was after him. I stood there dumbfounded as I looked at those tracks. I could not figure it out for a while. In fact, as I remember it now, it was not until a few days later while I was taking the set up that the answer came to me. I had gotten into the same position I had taken when the set was made in my attempt to fathom the cause of the fox’s flight when I noticed my face was very close to the bushes. I had taken considerable time to make the set and I could see now that I must have smeared those bushes well with my tobacco-laden breath!

We all will quite readily agree that a fox can detect human odor where the hands come in contact with any object, but just how much odor can you to detect on the dry clean hands of any trapper? Not much, but take a whiff of his breath, if you are not a tobacco user and he is, and you will smell tobacco plenty loud. Even if not tobacco, there are likely to be other odors, and in rare cases those odors will compete favorably with that of the most stinking fox bait. The human breath is laden with moisture. For proof of this, step up to the mirror and take a deep breath and exhale it on the glass. You’ll quickly understand how all of the odors in the breath can adhere to any object that it comes in contact with.

While I was in the trapper supply business I had a steady demand for mason trowels. Trappers were using these principally for making water sets for fox. The majority of the land trappers would not buy these short-handled trowels. Nearly all of them had the same story. They wanted a trowel or small hoe with a long handle as they did not have much luck with sets made with the short-handled trowel. To me the answer is simple. The water trapper is in the water while making the set, and if his breath does settle down to his feet it is quite likely to settle on the water away, whereas in the field with the land trapper the breath strikes the ground and scent to remains there.

The general run of water trappers whom I have talked with agree on a certain point: sets made for fox in brooks or springs where small bushes are quite abundant never seem to produce many foxes even though the trapper gets in and out without touching any bushes with his hands or body. Again, the answer is that breath. If there are small bushes or long stalks of grass in front of you, they are sure to be well plastered with that damp, scent-laden breath unless the utmost caution is used by exhaling the breath such that it comes in contact with nothing near the ground.

It is my belief that the majority of successful fox trappers are very careful with their breath, yet I think most of them do so unconsciously. For instance, if most any one of them were to give the personal instructions in the making of a set the chances are 100 to 1 that they would not mention the importance of guarding against the scent in your breath while making a set. If my memory serves me correctly, I can recall only one trapper who has stated emphatically in his writings importance of preventing the scent of the breath from coming in contact with anything near a set. Jim Mast does so in that wonderful book of his: “Coyote and Wildcat Trapping”.

“Shucks!” I hear someone exclaim. “Trappers are making large catches who have never heard about this scent from the breath being a danger to guard against”. I admit that is all very true. Fortunately, there is an existing condition pertaining to the human breath that is most favorable for trappers. The breath is warm and warm air rises quickly, and unless the face is quite close to the ground, or some object near the ground, the force from the lungs will not send that warm air down sufficiently to contaminate the set. Nearly all land trappers are far more successful when using a long handled implement for making sets, consequently their face is some distance from the ground. These trappers, however, as a rule have had little success with their land sets for foxes back in the woods where there are plenty of twigs for the breath to adhere to. There are a few who do take a considerable number of foxes from land the sets in the woods, and I think that such, either consciously or unconsciously, are very careful where that damp, scent-laden breath is blown.

Find this stuff interesting? I’m working on a book covering the works of Walter Arnold, the legendary trapper from the Maine woods. Stay tuned, and contact me at jrodwood@gmail.com to reserve a copy!

Leave a Reply