Trapping beaver through the ice is one of my favorite things to do. It’s also without a doubt the most labor intensive type of trapping one can participate in. The changes in population status and pelt value between Walter Arnold’s time and today are more evident with beaver than any other species. By the 1950’s, beaver were still recovering from decades of overharvest that contributed to severe population declines. Their pelt value was so high that trappers went through considerable effort to target beavers. The species made up a significant portion of most trappers’ paychecks. Today beaver populations throughout North America are as abundant as they’ve ever been, and some might argue that beaver densities are at historic highs. The pelts are hardly worth a thing in the market, and restrictions on beaver trapping, including seasons, method of take, and bag limits, are incredibly relaxed. Where I trap in northern Maine, we are able to trap for beaver six months out of the year with no bag limit. Additional relaxing of beaver trapping regulations is being considered in an attempt to minimize the damage caused by an overabundance of the rodents. Because of the low pelt values, few trappers are targeting beavers, and those of us who do get out there have the good fortune of minimal competition with other trappers.

Much has changed in beaver trapping over the past century, but much remains the same. Though we now have the convenience of snowmobiles, power ice augers, light chainsaws, newer traps and a great deal of shared knowledge of methods throughout the trapping world, beaver trapping and pelt handling is still back breaking work. The challenge remains, and the excitement of trying new sets and continually honing our skills at taking beaver through the ice still drives trappers today. Below are Walter Arnold’s reflections on beaver trapping from an earlier time.

Under Ice Beaver

First Published in Fur-Fish-Game March 1952

Walter Arnold

If one is interested in knowing what can be done toward a nearly exterminated fur bearing animal, and as in some of the states, make that animal the backbone of the state’s fur industry, about all he has to do is to study what was done for the beaver. Most of the answer was the enactment of enforceable protective laws – laws with teeth, which enforcement officers could use and in most cases bring about convictions against violators they apprehended – laws without a thousand loopholes. Beaver have been brought back to the extent that entire states and vast areas in others are opened up to trapping each year. To many, it is now not a case of bringing them back, but how to trap them.

Open Water Beaver Trapping

The open water trapping of beaver should not greatly tax the skill of any professional trapper of the other water animals. Beaver are as easily taken in runways or with bait or scent sets as the muskrat. Being built along about the same lines as a muskrat, they may also wring off when caught by the front foot, but as a general rule not near as quickly as Mr. ‘rat. If traps are visited every morning there is little likelihood of losses.

There are a thousand and one different methods of rigging up drowning sets, bags of rocks, sand or whatnot fastened to the trap, and many other ideas. However, if one was to follow most any professional beaver trapper around, I don’t believe he would be seen fooling around and wasting time with some of these contraptions. Some of them are no more sure fire than the trap itself. In fact, if a four or five foot length of telephone wire is attached to the trap ring and used as an extension chain so that the animal will have opportunity to chase around a bit, it will aid a great deal in cutting down losses. Then of course there are many places where the open water sets can be made where there are logs, roots or brush under the water, and if an extension wire is used, the beaver will in its struggles get down under these, tangled up and generally drowned. Then again, if he gets the chain wound around a stake out in the water so he has to stay in the water he is not near as likely to pull out of the trap as when he gets hung up on land.

No, the average professional beaver trapper, making sets in open water, is not handling tons of rocks or sand, or other heavy weights in putting out anywhere from 50 to 250 sets. If I were to make a business of using drowning devices, I believe that I would just step out and buy some of the light weight devices being made for that purpose. Then I would study out the most practical ways of fastening these to the bottom in deep water. I am sure there would be many places where I would use only a lightweight fox grapple.

Although our beaver trapping here is winter work, we do find now and then places in spring brooks, and other places where open water sets can be made. Quite often there will be a nice place but very little water, where a drowning set could not be made with any sort of a rigging. At these places I usually put out two or three traps, fastened so that it is impossible to bring two traps together. I like to figure around twenty inches to the nearest they can be brought to each other. Then when the beaver gets into one, he is not springing the others with the trap that is on his foot. Once in a while he will spring them with his body and not get a foot into them, but as a rule he will have at least two feet in traps. I have taken them with three feet in traps. They don’t get away under those conditions.

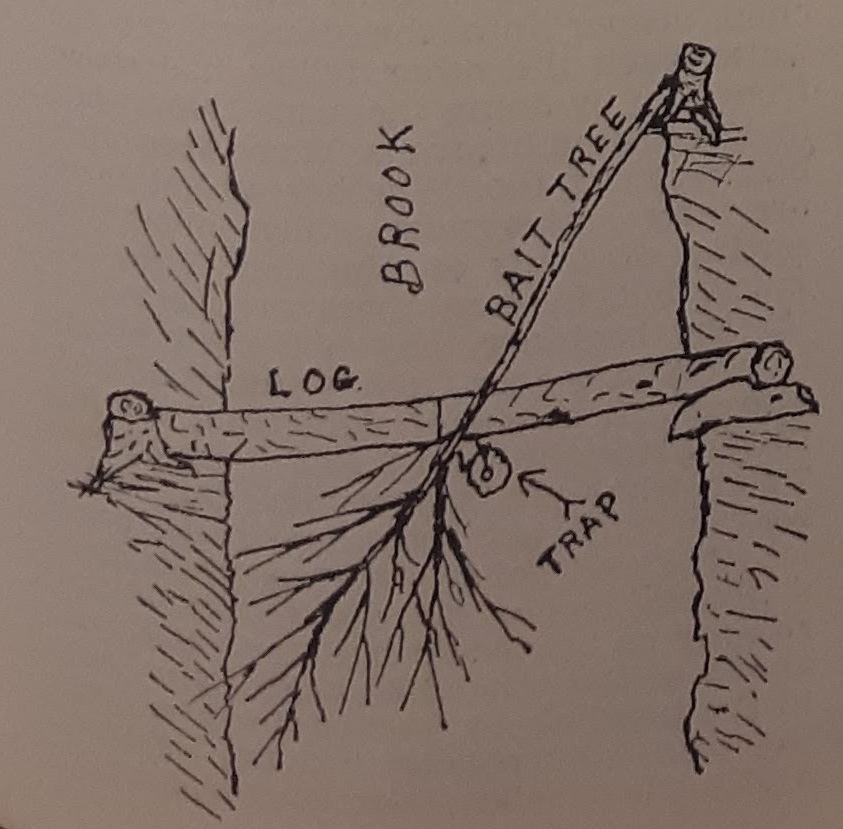

Nearly every place where an open water set is to be made is a bit different in some respects than other places, and presents different situations and obstacles to overcome. One must be able to do some serious thinking and study out ways to get around these. There is one general setup that presents itself in somewhat the same way quite often: after the flowage has frozen over, there remains open water in the feeder brook running into the flowage. Here is how I handle that situation if the water runs from a few inches to a couple feet in depth. Usually nearby will be the trunks of trees, six to eight inches in diameter, the beaver have left after taking the tops and branches. From one of these is cut a log the right length and dragged down and laid across the brook so it will lay with the bottom side touching the water. Then a bait tree with plenty of brush on its top is cut, usually I wind up with a moosewood that has a long trunk without branches for two thirds up the body. This is laid so the butt can be fastened to something on or near the shore, up the brook from the cross log. It is long enough so it can be placed on an angle pointing downstream and toward the opposite shore, with possibly the top branches touching the shore, but in a manner so that it crosses midway the cross log about where the first branches shoot out from the trunk. Sometimes it is necessary to trim off several of the lower branches to make it come right. This will now leave one side of the bait tree easy to approach from downstream. It may be necessary to trim off a branch or so, on what is to be the approaching side where the trap will be placed. Nail the bait tree to the cross log. The trap is placed three or four inches under water right where it looks like the beaver’s front feet will be when he starts to cut this bait tree off at the log. Sometimes it is necessary to build up a trap bed with a big flat rock or whatever is convenient. The trap chain is fastened about midway of the cross log so the beaver cannot get onto dry land with the trap. The first night they may snip off a couple of the limbs out near the top, but sooner or later and many times the first night, a beaver will come right up to steal the whole works and start to cut it off at the log. I have taken many beaver with this set.

Under Ice Beaver Trapping

Under-ice trapping, especially under present conditions, is a far cry from open water work. For instance, mid-winter trapping in states subject to a great deal of sub-zero weather, with ice running from 18 inches to four feet in thickness and sometimes several feet of snow drifted in where sets should be made, is in itself a condition that will provide the trapper with no end of back breaking work. Then there are colonies of beaver that will show little or no interest in the nice things we trappers put down there for them to feast upon. Come to think of it, there is no end to the obstacles one runs into.

The early days

I well remember back to the days when first I went into beaver trapping here in Maine. Many of us had our traplines well back into the wilderness where there was little or no competition, and we respected each other’s territory. Whenever our traplines were opened up for beaver trapping the season usually ran from sometime in early December, right through to March 1st. We were not forced to study out sure fire sets in order to beat out time or someone else. Usually there was a bit of open water trapping at some of the colonies during the first of the season and we would make some easy catches here, and also start picking up some in our under-ice sets. But soon the pattern would form, here and there would be colonies where they were slow to take bait, at other places we would find traps sprung with maybe a toenail in them and these beaver would start being cautious. We didn’t worry any, figuring they would come to bait later in the season. We would keep at it, picking up pelts now and then, finding baits gone and what not. But sure as fate, about the middle of February the sly ones would start showing interest in our offerings. How many times that last week and even the last day of the season I have seen the last sly holdout of a colony fall victim to our sets. Their own feed piles had become sour and slimy, and they just couldn’t resist those fresh clean baits we would put down for them the last few days of the season. In this way we were taking pelts during the entire season, which meant a steady income and it all worked out fine. Some of us even thought we were getting pretty good at it.

Things get serious

Then, along came a change in our Maine beaver law. Territory now opened was only from January 1st to February 7th. Competition was becoming keener. It wasn’t long before some of us realized that if we were going to remain in the game we must get down to more serious business. At some of the places, if we did not get Mr. Beaver right off quick someone slse had him, and beaver that got scared the first of the season, in many instances, were not ready to come back for another chance before the season ended.

Learning experiences

One fall while trapping other animals, I did a great deal of thinking about this matter. I realized that I had fooled around with some types of sets that probably never could be developed into sure fire sets. As I studied the matter I realized I had done many foolish things, such as making some of the post sets in deep water and having the bait and trap on the post way down close to bottom, where in some cases the pole had to be pulled out to see if the set was okay. Other sets not quite as deep, we would lay down on our bellies trying to avoid getting wet from the slush, remove our hats to use in shading the light in the holes, with snow blowing into our hair and sometimes we would be using a flash light. After lying there five or ten minutes our eyes would finally become accustomed to the darkness and we could make out just the faintest outlines down there. Usually we could see the bait and if it had not been disturbed we felt sure there was nothing in the trap which we could not see. We would take a chance that everything was okay and move on to the next set and repeat the performance. Many of us trappers did all that, just why I probably will never know.

I also realized that in many cases I had been fooling around with sets with traps too far away from the baits. Another thing, many of us were going to all the work and trouble of cutting poles far larger and heavier than necessary. I never yet had a beaver cut off a pole, or try to, under the ice after he got into a trap. He is far too busy trying to get away from the trap. In most cases the large posts are just a waste of good timber. There has been more than one landowner who has petitioned to the Fish and Game Department to get his land opened up so the beaver that are doing him damage could be trapped off, and then after the season was over has looked the place over, especially when there had been six or a dozen trappers operating there, cutting big posts, cutting down, each his own big poplar tree to get limbs for bait, the landowner has sadly shook his head as he walked away, muttering to himself “The trappers cut down more good timber than the beaver did”.

Well, getting back to the topic, I studied back over past experiences and when the season opened that winter my plans were all laid. I had figured out three different sets, all a bit different than I had used before, and I was going to stick to them and find out what was what. If I got beaver all right, if I didn’t all right. There was one set I was in hopes would not prove to be the right one, as it required considerable time and work, and that was one of the things I wished to get away from. It was this one:

An elaborate set

I would cut two poles about 3 or 3 ½ inches in diameter where the set would be made. After testing to see how far they would be shoved into the bottom of the pond, to find out exactly where the trap should be placed, I would lay them down about six inches apart, and nail a solid stick about two inches in diameter across the poles, like nailing on a ladder rung. Now the sticks forming the trap platform were nailed inside the poles and so they rested down on the cross stick. These sticks were long enough so they formed a platform on each side. Another cross stick was nailed across the poles above the platforms. This made the set steady and firm. This last cross stick was placed where the bait was to be fastened on. The brush baits or bait sticks were now fastened on above the traps and this made up sort of a double barrel set with a bait and trap on each side. Beaver could approach from either side and could also see through the set. I had wondered if they would be less wary of a set they could see through. I now do not think it makes any difference. Needless to say, a big hole must be cut through the ice to get this set placed. This set did work and I had no misses with it. It took every beaver that fooled around it after the bait. However, I do not use it now as I have found something far more practical. The traps were placed up close to the bait, just far enough back so the jaws would not catch any of the bait sticks when sprung. No, the trap was not shoved in under so the pan was under the bait. The far end of the trap would be just about even with the outside bait sticks. This set was placed so the poles stood straight up and down.

A failed experiment

I did not think too much of this next set when I was preparing it, and only put out three of them, I believe. That was sufficient. I would cut a couple of small poles as in the above set. After testing for depth so as to know where to place the trap on the poles, I would lay the poles down about six inches apart and nail a solid piece of wood across them. Now this set was to be placed on quite a slant in the water so the trap platform was nailed to the cross piece in such a manner that the trap would set level on it when the set was finally placed in the water. Another cross piece was nailed across about where the bait would be fastened on if it was a brush bait. If the bait was to be sticks of bait wood, then the cross piece was nailed so it would be above the ice when the set was in. This was to hold the set firm when handled. The bait was down close to the trap and put on across the poles, either wired or nailed on.

This set looked as though it might work out all right when it was set into position, but it did not. Traps would be sprung with nothing in them. At one colony it was sprung twice right off the first three days, after that the beaver would not look at any kind of a set for the rest of the season. I really don’t know just why I did try this set anyhow, unless it was because I never tried anything like it before. It didn’t work for me, that’s sure.

The practical set

The next set is one I had devoted a great deal of thought to, and had figured it would be by far the most practical and efficient of any I every used. It proved to be just that. I used a light pole, dry or green spruce, cedar or fir, about three or four inches in diameter at the part where the trap and bait were placed. Now behind where the bait was to go would be the back side of the post, and across the post, in this notch, was nailed a piece of dry limb sixteen or seventeen inches long and about an inch in diameter. Spruce was my preference. Beaver want nothing to do with spruce, and will go after the bait from the front side. For bait I used either a big bunch of tender small branches from moosewood, poplar, birch, etc., anywhere from half an inch in diameter down to the fine tips. In making up the brush baits I would make up a big bundle about seventeen inches long and four inches in diameter, leaving small tips sticking out from the main bundle. The bundle was bound together with dark stove pipe wire, by winding the wire around each end of the bundle, leaving the whole distance of the center good clean wood, free of wire, nails or other metal for the beaver to get his teeth on and discourage him. Then I would lay this across the pole on the opposite side of the dry cross stick on the back, then bend the ends of the bait bundle back and fasten securely with wire to each end of the dry cross stick. That is why a back cross stick should be one with plenty of strength. Use plenty of wire at each end and get the bundle on solid.

In making the trap platform, each side of the post was hewed just a bit to make a flat surface where the usual platform sticks could be nailed. The trap was placed on the platform so it was right in front of and close to the post and adjusted so that it would miss catching any of the bait sticks when sprung. For years I used soft brass wire to fasten traps to platforms. Now I use a couple short pieces of stove pipe wire, one at each end of trap. The wire is pulled down tight and then twisted together with about one turn, just enough to hold the trap, but something a beaver will soon yank out. For the last three years I have used mostly just a single chunk of dry cedar, hewed out the right shape for a trap platform.

Today when I put together this set, all I require is one light pole, a dry spruce limb and a small chunk of dry cedar. Of course bait and trap are required, but nevertheless that is getting down to something light and practical. When the pole is pushed into the bottom of the pond where it is to remain, the bait on the pole is about six inches below the bottom of the ice and the pole stands straight up and down. This makes a set that is easy to put together, does not require a big hole through the ice, and one that is easy to see once it’s placed under the ice. I have used this type of set for several years and never yet have had a beaver steal a bait without getting caught.

Set security

After any kind of a pole set has been put in, it is good insurance to find a heavy chunk of wood three or four feet long and lay it down on the ice so it runs about flush with the back of the hole. The pole the set is on is then pulled over against this wood and wired to it, so if a beaver gets into the trap before the pole freezes in he is not going to work the pole free and swim away under the ice with the whole set. Many beaver have been lost by trappers who failed to take this precaution. Additionally, if the trap ring is fastened as far down on the pole as it will reach, it will aid in holding the animal under the ice until it drowns.

More set details

The above set may be baited with either brush or solid chunks of bait wood. The bait sticks, anywhere from three quarters to two inches in thickness and around sixteen inches in length, are nailed to the front side and crosswise on the pole, one above the other and so that an equal length projects from each side of the pole. Two or three are nailed on, depending upon size and then usually another one, sometimes a bit shorter, is nailed right onto the ones on the pole, this last one is generally placed a bit slanting so it touches on all the under pieces. The upper end of this stick should not stick up above the under sticks, but it is okay if the lower end of it sticks down an inch or more below the under bait sticks. The trap platform is placed so the trap will set close to the pole, but so the jaws will not catch any of the bait wood when it springs. In using my #14 Victors, I find that having the top surface of the platform about four inches below the bait will bring the trap into about the right position. If the bait is large and protrudes four or five inches out from the post, the trap should not be shoved under it so the pan is under the bait.

A variety of this set, one I am turning to more and more, which requires less bait and a smaller hole through the ice, is made with this slight variation. Instead of the long wood bait sticks, sticks about a foot long are used. These are nailed to the post so that they project all out to the same side, for instance the right side of the pole, with no bait wood sticking out from the left side. The trap is placed in exactly the same position as if the bait was projecting out from each side of the pole. This is not a brain storm set, but a real beaver getter with few misses.

Bait for beavers

Before placing a bait onto a pole it is good to hew a flat surface where the bait is to be nailed on, also hew and flatten out that part of the bait stick that is to be placed against the pole. That being done, it only requires a couple of small nails to securely fasten the bait to the pole.

The use of the right kinds of baits is one of the most important factors in successful under ice beaver trapping. I would make no attempt to tell anyone what the best bait is because I do not know. Not even right here in this small section of the country. What I mean is this. Some seasons a brush bait, such as a bundle of the tender branches of moosewood, birch, poplar and other trees will be taken readily. Then again, there are times when they won’t look at a brush bait for me, but will seek out the wood baits and we are not always sure which of these they want. Some of the wood baits are poplar, and by that I do not mean balm of Gilead, for which many of us have no use for at any time. Then there is moosewood, the birches, willow, brown ash, maple and others. Year in and year out I think that poplar, or as we call it here popple, is the most widely used and takes more beaver in the state than any other bait. However, time and again I have seen cases where beaver would be ignoring brush baits, popple, moosewood and others and then we might for instance turn to white birch and shove down a couple sets using this for bait and start getting them. I remember an instance where three trappers were trapping around one colony where there were two very old, large beaver. They were all good trappers and had good sets with a variety of baits. They got not even a nibble. One day one of these trappers going to the sets noticed a wild apple tree in the woods near a back opening. He stopped and cut out some of the small, green limbs and used them to put in two sets. The next day he had both beaver. That did not mean that apple tree was the best bait in the state, it only meant that it happened to hit those two beaver in the right spot.

Trap platforms

Several varieties of trap platforms are used on under ice sets. Sometimes a forked stick the right size and shape is used. The butt of the stick is nailed to the post with the fork sticking out in front of the post, and the trap is fastened onto this. The right size and shape is not always easy to find, and even then is not always satisfactory. Then there is a method in which no platform is used. A saw that has been set to cut a scarf the right width is used to saw about 1 ½ inches straight into the side of the bait pole (using a five or six inch pole). Then a #14 Victor (this seems to be the type of trap that works well with this set) is set and the end of the spring is pushed securely into the saw scarf. I have never used this method but evidently the trap will spring and make its catch with the spring held in the scarf. The beaver in its first struggles will pull the trap free. This method makes it necessary to carry around a saw with all the other beaver trapping equipment. It is little used.

A few years back the majority of the pole sets were made with the pole standing at quite a slant. Large poles were generally used and a notch was chopped into the pole so that a trap lying in it would be level when the pole was set into position. Often the notch would not be large enough but this was taken care of by nailing to the lower lip of the notch a chip the proper length and width to provide the space required. The platform used most widely is made with two small sticks the proper length, depending upon the size of the pole and the type of trap used. These sticks are nailed one each side of the pole, opposite each other so that when the pole stands straight up they will project straight out and the trap will lay level when fastened onto them. Ends of these sticks should not be sticking out beyond the trap as they may just provide a resting place for the beaver’s foot so he never will contact the pan of the trap.

In attempting to cut down on extra work, make sets light, compact, effective and quick to construct, I have been turning more and more to using just a single piece of wood for a platform. I make these at camp in my spare time and when my fingers are not numb with cold. Just split out some blocks of dry cedar, one foot long, two and a half inches wide and about an inch and a half deep. Now back about four and a half inches from one end, hew in and split out enough wood so there will now be about 4 inches of the block that is 1 inch wide and 1 ½ inches deep. This is the part that will be nailed against the side of the bait pole. Now this will leave about eight inches of flat surface two and a half inches wide sticking out from the pole. This eight inch part will be an inch and a half thick which is too much wood, so hew out enough from the underside so this part of the platform will run from a half inch thick on the end to three quarters of an inch back six inches. As this may not be easy to understand, I am submitting a picture of one fastened to a pole. These platforms can be made at camp and then put into a kettle of maple and alder bark, add water and bring to a boil-then allow to sit over night and take on color. This kills all the new axe marks. After a solution has been made a fresh batch of platforms can be colored each night. After they are dried out they are very light to carry and save a great deal of time out on the trapline. I mention a foot length, this I find is about right for my #14 Victors. With different sizes of traps one would be required to ascertain the length needed.

Working smarter, not harder

This three piece set, as I call it, is a far cry from the old days when even the professional beaver trappers would cut huge poles through the ice and gather up large quantities of old wood to construct under water pens to make their sets in. These elaborate sets were made to keep beaver from stealing bait from the rear of the set. I used to do it too. Now my theory about shy beaver sneaking up in back to steal a bait is that there is not one in a thousand that will do it. If a beaver is afraid of a set he is keeping away from it. If he is not afraid, he is going to take that bait from the easiest angle. My experience has been that when a beaver takes a bait from the rear it is usually because the set is facing the wrong direction. In making sets around in the main waters of the colony, sets should be placed so they face toward the house or den. Of course, in potholes and channels off the main waters it is not always easy to figure from which direction they will approach, but there are not many such cases.

Trapping on dams

It wasn’t so many years ago when we were allowed to set traps on beaver dams here in Maine. It was finally prohibited as too many trappers would fight for the water, and in a few days would have the flowage drained out. Two or three would have sets on a dam and every time one came around to visit his traps he would chop deeper into the dam to get the water back the other fellow had stolen from him by doing the same thing when he last visited his traps. There were other bad features too. Whether or not there are any states now which allow the setting of traps on the dam I do not know, but in case there are here is a tip the beginner may not know about, to prevent beaver from wringing off and also get them out of sight from any fur thief.

Place the trap two to six inches under water, whatever is convenient, where the beaver come out from under the pond ice. Try and get the trap so the pan is a couple of inches off the center of the runway, as beaver do not travel one foot ahead of the other like a fox. Now back in the pond about four or five feet from the trap, sink a hole through the solid ice and push a solid stake down through and into the bottom of the pond. Kick snow back into the hole so it will freeze solid. Now when fastening the trap to something on the dam use some telephone wire for extension so there will be around six and a half or seven feet of chain, trap and wire. When a beaver gets in and starts swimming around under the ice he is quite sure, sooner or later, to get the chain wound around the stake and get hung up solid where he is likely to drown right off quick, and out of sight.

Other set details

Conservation officers will want to know who has traps set where. The sets can be marked by placing the necessary information on tags and fastened to the top of the poles. Quite often, back here in the woods, all the trapper does is to hew a spot on the pole and write his name on it.

After under-ice sets have been made, kick the chopped up ice back into the hole along with some snow. If there is a lot of snow on the ice it can be heaped over the hole so it will not freeze as deeply in sub-zero weather. However, it is desirable that the hole does freeze over solid enough so that a beaver which happens to be caught by a couple toes or by the tail cannot reach up and get air and stay alive. There are few such cases, but a couple years back we lost a beaver caught by the end of the tail. It was during a thaw and the hole had not frozen over. The beaver could get up and get air, and finally twisted off the end of his tail. The old #14 was holding fast to that little bit, but it was not worth a nickel to us. It is also essential that the pole is frozen in, as a big beaver once caught will put on a lot of power down there the few minutes he lives.

After the catch

When a catch has been made and the dead beaver is pulled out onto the ice in sub-zero weather it is wet and will soon have more or less ice frozen to the fur. Most of the experienced trappers know what to do in this case if there is light snow handy. Get the beaver out of the trap just as quickly as possible and then start rolling it in the light snow. Pick it up and shake it and then roll some more. With a little work, most of the moisture is absorbed by the light snow, which means a much drier skinning job and a cleaner pelt for the pack.

Beaver fur handling

There is one characteristic in handling beaver pelts which reminds me of fox trapping. Back in the hey-day of fox trapping there were thousands of trappers scattered across the continent, each making record catches of sly old red in his locality, and in a great many instances each trapper was using something different for a scent than anyone else. A favorite formula might be a paste of rotted fish, skillfully blended with blue grass juice with a dash of lovage added, or it might be a mixture of snail oil and lion’s tallow pepped up with a few drops of essence of mermaid. But whatever the concoction was, the trapper taking more foxes than anyone else in his locality believed down in his heart that his lure was the only one in the world worth a hoot.

When it comes to fleshing beaver pelts there are nearly as many variations in the methods of fleshing as there are in the fox scents used. I started out using a sharp, four and a half inch thin blade hunting knife. I just skin the whole mess off the pelt and then with a larger knife, having a heavy, rounding belly blade which is kept dull, I scrape oils and juice out of the pelt. When I get through I have as nice a looking, undamaged pelt as the next fellow, but I know now my method is a slow one.

Among my friends are those who use an old scythe cut off at each end and made into a fleshing blade, or other types of improvised blades. Some use fleshing tools sold by trapping supply houses, while others have different homemade equipment, even to include devices to hold the pelt while it is being fleshed. One fellow has a little board something like a narrow, wooden muskrat stretcher and has a special way of holding it in his lap or along his arm with the pelt over it. He goes after it with his hunting knife and when through has done a mighty fine job of it. My trapping partner two years ago had just an old paint scraper, with corners rounded a bit, and the way he could roll fat off a pelt with that was a revelation. Why don’t I use that? Well I tried and got no place with it. However, now and then I do use it on a small pelt. I am gradually getting used to it and the tricks that go with it. Eventually I suppose I will acquire all the knacks that go with it and will use nothing else, but right now I can still do a much better job with my knife. After all is said and done it simmers down to this: it requires a lot of practice to get used to any method. Many of us have stuck to our own method until we know all the ins and outs concerning it and the work comes natural. A beaver pelt is not the same all over. There are easy places to flesh, tender spots in the hide, those tough places near the ears and front legs, the tricky hind leg holes to work around, and places down the back where one can scarcely make out what is pelt and what is not. Then there are pelts that just naturally flesh easy while others battle you every minute. Now and then we come upon a pelt that has old scars in it. Extreme care should always be exercised around these places, as they may or may not be as strong as they look. It only requires a couple of holes or cuts in the right place to cut dollars from the value of a pelt.

To those new to fur handling, about to do their first work with beaver pelts, here is some advice. First, when taking the pelt off the beaver be sure to leave a layer of fat or meat all over the pelt, do not skin down to the pelt at any place. Then, making sure there are not chunks of ice, sticks or other bunches in the fur, lay the pelt onto a big stretching board which should be smooth and without wide cracks between the boards. Using a few nails, stretch the pelt out tight and start skinning the fat and meat off. After some has been removed it will be noticed that the pelt is slack or loose. Pull out some of the nails and tighten it up again. Keep the pelt tight all the time until the job is finished. Then, using a dull edged knife or scraping tool, scrape off any small spots of fat and what juice that can be forced out of the pelt. Then remove all nails and stretch for shape. Pelts can be stretched perfectly round, but one is not likely to get the measurement out of a round pelt he will out of one stretched three to seven inches longer than it is wide. My experience has been that when one stretches the pelt perfectly round he loses mileage. A fleshing and stretching board 38 inches wide and 50 inches long will handle most any of the pelts. When stretching is finished, the nails should be a half inch apart.