The otter is a fascinating furbearer. Both playful and fierce, this water-dwelling, fish-eating mustelid makes long circuits through its home range, typically over the course of several weeks. Its long range movements combined with varying habits can turn otter trapping into a game of low percentages. But with enough practice, the patient and intuitive trapper can master otter trapping.

In modern times, the otter has been the subject of conservation success stories in numerous states. At one time over-harvested and scarce, otters have come back in big numbers, and many states have recently re-opened trapping seasons for the species after decades of closures. That means more trappers have the opportunity to pursue otters these days, and for many the learning curve is just beginning. In this article, Walter Arnold shares his experiences from more than three decades of otter trapping, and gives his thoughts on otter behavior, as well as some unique sets that have helped him pick up extra otters on the trapline.

The Otter

First Published in Fur-Fish-Game September 1947

Walter Arnold

Throughout this land there are legions of expert trappers. Thousands of them can talk shop with the sharpest fox, others know how to outsmart the craftiest coyote, and the experts who can clean out the bulk of mink, beaver, raccoon, muskrat, skunk and weasel from any trapline would make up an army of many divisions. But those who know anything worthwhile about the otter are few and far between.

There are several reasons why there are not more trappers who can truthfully say they understand this valuable furbearer. First, few have had the opportunity to study and practice on this animal, as many trappers do not find the otter along their lines. Even where they are present, one or more otter may make just a couple trips across the trapline during the entire season, and it always seems to me they make these trips during a flood or freeze-up, when the whole trapline is out of order.

Second, this elusive fellow is by no means what you can call dumb. He has a very sharp eye and a keen sense of smell, and if he has had a foot in a trap before, then a set must be well made or he will shy around it.

Third, the otter has no trouble at all in catching all the suckers or other sluggish fish he wants, so seldom is interested in bait unless it is absolutely fresh.

Fourth, he delights in sliding along with the front legs held back against the body, and the beginner’s traps are more likely to be sprung by his breast than by a foot. It’s pretty hard to get a foothold when the feet are not being used.

Fifth, he is very strong and has a very tough, slippery, tapering leg and foot, and unless the trap is powerful gripping, he will pull out and continue along his way a little wiser.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, it is easy to understand why there are not more good otter trappers. Although I have been trapping for them for over 35 years I do not claim by any means to be an expert, as there is much more I would like to know about this particular branch of trapping, and am not posing as an authority on the subject.

One winter, some 37 years ago, an extra large male otter was making one and two-day excursions up through part of my trapline at about two-week intervals with his signs showing up mostly around the inlets and outlets of certain ponds. There was too large an area of open water in these places for me with my meager knowledge of otter to figure the old fellow into some nook or corner and into a trap.

After the otter had made several visits, I noticed there was one large log, among many others in one of the outlets, that he went into every time. Knowing that he was a shy one, I waited my time. One morning I awoke to find that a snowstorm was in the making. Taking a strong #3 jump trap, I hustled onto the trail and headed for that pond. It was snowing when I arrived, and I soon had the trap well placed on the proper log, and did not cover it, as I knew the cold dry snow would do the job perfectly. It snowed about five inches, which was just what I had prayed for. I remained away from that set until I saw tracks on the ponds above, telling me he was on his way. The next morning I went down to see what had happened. There he was, just about the largest otter I have ever taken.

This catch gave me a great deal of confidence, then thinking I knew all about otter and was ready to clean up any and all I could locate. But alas, down through the years I have never again had all of those conditions presented to me at one time. I have found otter trapping in general to be something along the above lines. One comes across their works and then it is a case of finding out what they do and where they go while in the immediate locality. If they remain for two or three weeks, an observing trapper can usually study them out and find proper places for sets, but if they just pass across a trapline once or twice a season, spending only a day or so a trip, a fellow does not have much to work on. He must then be both lucky and a pretty fair trapper to pelt one of these hard skinning creatures.

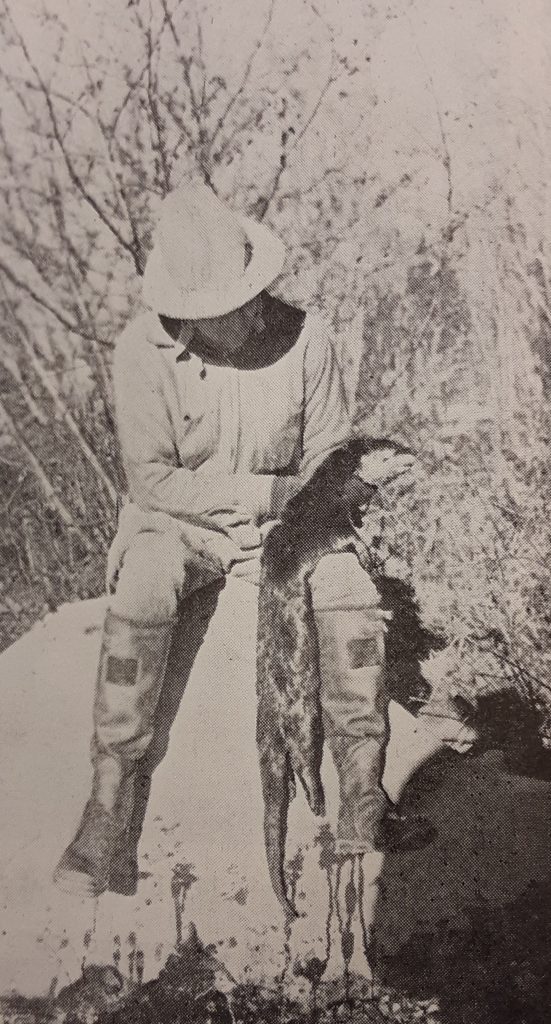

I have been fortunate in picking up several of these one-trip-a-year otter I have worked for. My former trapping partner Bill Gourley was good at this. I can see him now on a December morning as we were leaving camp, each to travel his own separate line, and hear him say: “Well, it’s about time for that old otter to visit such and such a pond on his annual trip. I have a couple of good sets waiting for him.” Bill made it very dangerous for the old wanderers and brought in more than one of them in our years together.

There may be localities where they are hanging around a single pond, bog or stream throughout the season, but such finds have been very rare for me. I have found them on several occasions, usually in winter, working a five or ten mile stretch of country. When this occurs, I have generally taken their pelts before the season was over.

Before the real freeze-up and winter snow arrive, otters like to get out and just play. Now and then their slides, or playgrounds, will be found on dry steep banks that slope off into the water. There will be a clean, well worn path free from leaves, brush, etc., down the bank into the water. As they are sliding into the water with their front legs against their body, it is not wise to set a trap at the foot of these slides, as they are likely to hit it with their breast.

On the top of the bank, one will usually find where they have dug up leaves, dirt, etc., into small piles and here their droppings may be in evidence. Traps set here are almost sure to frighten them away. Instead, try and find where they leave the water to climb back up onto the bank. This is not worn down like the slide, and may be hard to locate. Conceal one or more traps under water, close to the shore, as they will be using their feet when coming out. If there is a foot or eighteen inches of water close to the bank, set the trap down on bottom, and out six or eight inches from the shore, and try for a hind foot catch. If it is possible to see where they come out, then try to place the pan of the trap a couple inches off the center of the path. These sets can work, but my experience with them has been more or less guess work and a trust in Lady Luck to do the rest.

The playgrounds we like to find are those on bogs or in swamps. Moss will be found dug up into small heaps, and otter feces will be on these heaps or nearby. As a rule there will be trails through mud, shallow water, or moss around these places. Traps are placed under water or in the soft mud. If they are to be placed in the moss, they must be free from human or undesirable odors. Pans of traps, as in all otter sets, should be off the center of the trail. If there is nothing handy to fasten the trap chain to, a solid stake should be cut and driven into the ground. The chain is then fastened securely to this and then the stake is driven out of sight. Leave no fresh signs, disturbances or human scent about the place. As this animal does not travel one foot ahead of the other like a fox, but with the front feet apart, about the width of the body, the trap should be placed so the pan is an inch or two from the center of a trail or path. As they are sliding now and then it is well to find a stout stick ½” or 1” in diameter that has been traveled on by an otter If possible, and lay this across the trail at the end of the trap and about an inch above the ground or shallow water so the animal will have to come onto its feet to go over.

There is little chance of making a catch when the otter slides into a trap. It may hold a few breast hairs, and Mr. Otter is usually scared away for many weeks. I do remember one otter that did not take the hint, though. In the break of an old beaver dam, I had prepared a nice blind set for mink. I’d set a #1 ½ Victor below the face of the dam where a small trickle of water ran through, down over the trap. I never considered that an otter would pass through, but a pair did, and the old male slid down over the dam and pushed his face into the trap. It must have given him a scare at the time, as he left all the long whiskers from one side of his face in the trap. I immediately removed the small trap, replacing it with a large trap I had with me, placing it so the pan was at one side to take a front foot if he decided to return. Two weeks later he was waiting for me, the same otter, minus the whiskers on one side. Four or five miles beyond, I found his mate at another otter set in another old, abandoned beaver dam.

As I look back over the years I can see now that many of my most successful sets have been at old beaver dams. After two or three years these unused dams will rot down and wash away in places, forming some of the very best places for blind sets. However, the otter does not always use the most open places. Unlike the fox or other animals, they sometimes seem to delight in clawing up through a lot of brush, so it is not easy to always guess just where they are going to come over. The trapper has to keep his eyes open and find out such things.

I never use scents or bait at blind sets around the playgrounds, and seldom any at sets in the old beaver dams or other blind sets. I often prepare sets using scents or baits along the shores of small brooks, ponds or at old beaver dams some distance away from my blind sets. They are often interested in lures, and carefully prepared sets often produce results. Inlets and outlets of ponds are also likely places for bait or scent sets. Just place the trap under water, anywhere from one to six inches. Work a little old grass, water-soaked leaves, or even the full branch of a water-soaked fern over the trap. Then place a few drops of your favorite otter lure on a dry piece of wood near the water’s edge or even a foot above the water.

There is a bait and scent set several trappers have told me they have had good luck with. I have never accomplished much with it, but perhaps I have used blind sets where this set should have been used. Here it is:

Select a place you are pretty sure that otter will find. If there are plenty of rocks handy, use large sized ones to construct a rock cubby house with about ¾ of it under water. Inside dimensions should be about one foot wide, sixteen inches high and eighteen inches long, without a top. If rocks are not available, use pieces of old dark colored wood.

Fasten a piece of fish about ½ a pound to a piece of wire or small stake, and place this at the back end of the cubby, close to the bottom. Fish should be in as natural a position as possible. Place two traps close to the fish and up to about a level with the underside of the fish. Drop a few water-soaked leaves or ferns down onto the bottom with a few drops of scent on the part of the cubby that is above the water. Natural openings between old logs or between rocks under water may also be used for this type of set.

There is a crazy sort of a set which I have used that works pretty well. It probably would not be practical to use in localities where trap thieves are plying their trade as it is easily seen from a long distance. It is simple to make. Cut down a small tree natural to the surroundings. This can be anywere from an inche to three or four inches at the butt. Sharpen the butt to a point, and drive it into the bank so the tree leans well out over the water. Using a fine wire, fasten a quarter or half pound fresh fish by the nose to the wire, and then hang the fish from the tree so that the fish is about eight or ten inches above the water. Place a trap about four or five inches under water, directly under the fish. If water is too deep, build a base up from the bottom with rocks. In a muddy stream a stake with an eight inch square piece of an old board nailed to the top can be driven down so the trap can be placed on the board at the proper depth below the surface. This set may not interest every otter, but it will a lot of them.

Sometimes the trapper will find areas of soft mud several feet in circumference which otter wallow in, and it is hard to select a place for a set as they enter from every side. I usually put in a cluster of traps and take my chances. Sometimes a catch is made, and other times a trap will be found sprung, which usually scares the otter away.

We do not always get to skin all the otter that step into our traps. During the 1945-46 season my partner Walt Tozier and myself had five in our traps and lost two of them. One of these padded the pocketbook of Johnnie Sneakum. Another fair catch was lost through carelessness on my part. A trap had frozen in and I had to cut it out with my axe. The ice was worked off without springing the trap and it was soon reset in open water a few feet away. The next trip was a heart breaker. An otter had gotten in, and after struggling around a little, had pulled out and was gone. Somewhat disheartened, I started to reset the trap and found a loose jaw, which was broken close to the socket. I’d broken it when chopping the trap out of the ice. Had I sprung it before placing it in the new place, the break would have been discovered. Well, it’s no use crying over spilled milk. The damage was done and my otter gone.

One of our five otter that year was picked up quickly. Walt came in late one afternoon while we were cooking supper and remarked “There is an otter down at the little pond and something strange is going on”. Next morning we went down and sure enough, the water had dropped about a foot in the pond. Investigation showed that the otter had dug through the old beaver dam, letting the water drop. This gave him a lot of open space under the ice, also land under the ice to play upon where there had previously been several inches of water. There were a couple of small, open water places close to the dam the otter had used, so we put a trap into each one. I never went down again, but Walt reported the following two dys that the otter was coming out of one of these holes but seemed to know about the trap. “I’ll fix him” he said, and took down two or three more traps and placed them carefully around the location. The next day he came back with his otter. That is what I mean by saying that if they hang around, you can figure them out and get them.

The otter trapper should be on the alert with his eyes open. There is always something new popping up. For instance, I was going through one of those waterless swamps with lots of damp, soft moss, small bog spruce, scattering maple and birch, and the occasional clump of alders. There were no brooks or ponds within half a mile. I came upon a trail, and looking it over, decided it was made by otter. Selecting a place where it ran between two small knolls, I placed a clean trap in a depression in the trail, with the pan off the center of the trail. Back away from the trail I pulled up a handful of the long moss and worked it in and around the trap, doing a neat job. I laid the chain over to the base of a small spruce, and then pushed it down into the moss out of sight. The trap ring was securely wired to the spruce. A dead limb was laid across the path at the end of the trap, and about 2 ½ inches above the path. Clean gloves were worn in making the set and no fresh signs and very little if any human scent left about the place. No lure was used. A few days later I was rewarded with a good sized otter.

In making otter sets with lure, several different items may be used. Some of the old timers will tell you there is nothing better than fish oil. Others prefer beaver castor. Mink musk is a very popular item, and muskrat musk is often used. A good compounded lure can be made by mixing together one ounce of glycerine with one ounce of pure water, add to this one ounce of ground mink musk sacs, on half ounce ground muskrat musk sacs, and one third ounce of ground beaver castor. Add to this the musk from the first otter you get. Yes, otter musk is good, but is very hard to obtain.

As a rule it is advisable to use powerful #3 and #4 traps. The #2 Newhouse is all right, and so is the #2 Victor coil spring when new, but usually a wider jaw spread is desired. There are many professional trappers who prefer traps with teeth, and of course this does eliminate pullouts. Some states prohibit the use of larger traps, and in such cases, one should use only the strongest #2 traps. Take no chances with weak springs, as Mr. Otter will be the winner in a battle with such traps.

The otter is very strong and can pull hard, but is not much for gnawing, and seldom chews up a fastening stick the same as a fisher or raccoon does. They also have plenty of courage, and I have seen on many occasions where they have spent hours in a swamp where there were bobcats that were powerful enough to kill deer. I have never seen where the two have met, and have often wondered just what would happen if they did.

Find this stuff interesting? I’m working on a book – a compilation of the works of Walter Arnold, the legendary trapper from the Maine woods. Stay tuned, and contact me at jrodwood@gmail.com to reserve a copy!

Leave a Reply