Description

The American beaver (Castor canadensis) is the second largest rodent in the world, is semi-aquatic, and primarily nocturnal.

Along with skunks, beavers are among the most well known furbearers in North America due to the substantial, visible alterations they make to aquatic habitats. Beavers cut down trees and branches of all sizes, build dams with sticks and mud to create small ponds in streams, and build houses in deepwater areas of ponds, rivers and streams.

Beavers are one of the only furbearers that actually create their own habitat, and other wildlife benefits from the habitat created by these fascinating engineers. Beaver flowages provide refuge for fish, birds, muskrats, mink, and many other wildlife species.

Despite the positive wildlife benefits of beaver ponds, however, beavers can cause significant problems for humans and wildlife alike. Beavers can cut and kill valuable trees and plug road culverts and bridges at stream crossings in attempt to create dams. Beaver dams can cause passage problems for migrating fish as well.

Trapping plays an important role in controlling beaver populations and avoiding human/wildlife conflicts while ensuring a sustainable beaver population for years to come.

General Information

The beaver is an extremely large rodent; adults weigh between 30 and 80 pounds on average, and some can tip the scales at over 100 pounds! One of the more distinguishing features on the beaver is its large, flat tail, which is used to create a large splash in the water to warn other beavers of danger. The beaver also has webbed feet, which are very useful for swimming efficiently in water. The beaver’s coat is made of two types of fur. The longer guard hairs located on the outside of the coat protect the underfur and help shed water from the beaver’s body. The short, thick underfur keeps the body warm throughout the winter.

History

In the 18th and 19th centuries, demand for beaver pelts had an important influence on the settlement of the American West. Trappers and fur hunters could make good wages selling beaver skins, but the rewards did not come without a price. Fighting Indians and wild animals, and braving the brutal weather and terrain were all necessary to reap the financial benefits of the blossoming fur business. Over time, much of the West became settled and beaver populations declined throughout the U.S. due to over-harvest. Strict regulations on hunting and trapping beavers, combined with lower fur prices, resulted in the comeback of beaver populations nationwide.

Geographic Location

While their geographic distribution was once severely limited due to over-harvest in the early days of North American settlement, beavers are once again broadly distributed throughout almost the entire United States and Canada. In most of these areas today, beavers are abundant and often considered a nuisance due to the amount of damage they cause to human infrastructure.

Diet and Habitat Requirements

The beaver is an aquatic animal, needing deep water to protect it from predators. While some beavers build their dens by digging into a river or stream bank and cap them with mud and sticks, many others need to build dams that create the reservoirs of deep water for them to live in. Dams are usually several feet high and can be up to hundreds of feet long. At the deepest part of the flowage, beavers build houses of sticks and mud. The houses, often called lodges, are accessed through underwater entrances to avoid access for most predators.

Beaver flowages can provide beneficial habitat for other species like muskrat, mink, otter and fish.

Beaver diet consists primarily of tree bark from aspen, cottonwood, dogwood, willow and other tree and shrub species. In the fall, beavers cut their winter supply of food and store it in a large pile, called a feed bed, near the den entrance.

Reproduction

A single family of beavers, consisting of a breeding pair and two generations of young, usually lives together in a flowage. After their second year of life, young beavers are usually kicked out of the lodge. Beavers are very territorial and their territories usually do not overlap. Breeding takes place during mid-winter and the female gestation period is relatively short – only 107 days. Young are born in the spring, around the same time that two-year-old beavers are evicted from the lodge to find their own territory and mates. Between 3 and 5 fully furred and toothed kits are born in the lodge and quickly take to water.

Trapping the Beaver

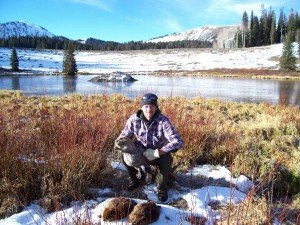

Beaver trapping is a very important part of American trapping history, and continues to be popular today. Images of the old time mountain man setting traps in a beaver flowage are often the first thing that comes to mind when most people hear about beaver trapping. While incredible changes to beaver trapping have taken place over the past two centuries, the basic idea is the same, and beaver trapping is still hard work.

Location and sign

Beavers are probably the easiest animal to locate based on sign. They sure leave lots of it. The most obvious sign of beaver are the large dams they build across streams. If you find a beaver dam with freshly peeled and placed sticks in it, beavers are not far away. After finding the dam, the next most obvious sign of beaver is the beaver lodge, or house constructed of mud and sticks that provide shelter and protection from predators. Lodges are usually built near the area of a beaver flowage where the water is the deepest, providing the best protection against land-based predators like coyotes and bobcats. Sometimes the lodge will be built in the middle of a flowage, while in other situations the lodge is built up against, or under the streambank. Some beavers do not build lodges, but rather burrow into the streambank and sometimes make at attempt to cap the muddy bank above the den with a protective layer of sticks.

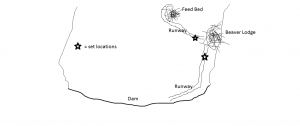

When trapping most furbearers, location is half the battle. The beauty of beaver trapping is that once you’ve found a fresh beaver flowage, trapping can be quite simple. If you find a fresh beaver dam and house, look for a feed bed. The feed bed is a pile of sticks and brush stored a short distance from the beaver house and it serves as the winter food supply, particularly in areas that are covered in ice all winter. Also look around for trails and travelways that the beavers are using. Early in the season trails will frequently go up on land. In northern climates, ice and snow prevent access to land all winter, so you’ll need to trap the underwater trails.

Beavers’ frequent underwater travels will often cause runways to be carved out in the muddy stream or pond bottom. You’ll find runways exiting the house, between the house and the feed bed, and between the house and the dam, among other places.

Traps to use

Beavers are commonly trapped using 330 conibear traps, #3 and #4 douple longspring and jump traps, and a variety of snares. Larger coilspring traps like the MB750 and the TS85 have become some of the better beaver foothold traps available. Sets can be baited or set ‘blind’ on travelways. Below are just a few examples of beaver sets. As always, check your local trapping laws and regulations to ensure that you are within the law when making any particular set.

Article: What’s the Best Trap for Beaver?

Article: What’s the Best Bait for Trapping Beaver?

Beaver Sets

330 Runway set – A 330 conibear is set near the bottom in a beaver travelway, usually exiting the house, surrounding the feed bed or parallel to the dam. The easiest set location is often right at the entrance of the house, but this isn’t always feasible and isn’t legal in all states. As the beaver travels in the runway, it swims right through the opening in the 330 and is caught.

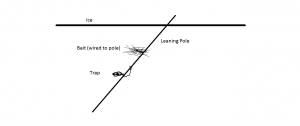

Baited Leaning Pole set – Bait (usually sticks of aspen) is wired to a leaning pole and a trap is attached to the pole a foot or two under the bait. As the beaver swims up to get the bait, it uses the trap as a platform to step on, and is caught. This is an under-ice set.

Baited or Unbaited Snare Pole set – Two snares are attached to a vertical pole, typically under the ice. Sometimes a couple of aspen sticks are nailed to the pole between the snares as bait. The pole can be set in the middle of a beaver run or in another area beavers tend to frequent. If baited, the beaver will circle the stick to get at the bait and be caught in the snare. If set in a run, the beaver will dodge around the stick as it’s blocking its path, and get caught in one of the snares. Often northern trappers will set many snares on a single pole. Snares are light and easy to set.

Castor Mound Set – In the springtime, beavers are exploring their territory and marking areas with their scent. This scent is produced by glands called castors, which can be extracted from harvested beavers and sold for use in perfume, or used as an attractor. Beavers make castor mounds, which are piles of mud heavy with castor scent, to mark their areas. You can construct your own fake castor mounds and nearby beavers will investigate them. Make the mound near the water’s edge and set a foothold trap in the trail approaching the castor mound. Where legal, many trappers use snares in these shoreline approaches as well.

Article: Beaver Foothold Trapping: Front Foot or Back?

Numerous other sets can be made for beaver, depending on the situation. The best way to learn new sets is to read trapping books and watch videos, and use your imagination to try new sets out on the water.

Fur Handling

Beaver are skinned open, by making a straight cut between the chin and tail, and skinning the pelt out from the middle. The skin is then fleshed and stretched in an oval pattern on a board. Numerous guides to fur preparation are available and can be found in the Fur Handling section of this site.